In 1971, psychologist Philip Zimbardo tried to prove the existence of crowd theory, also called deindividuation, which is a version of group madness. He turned a Stanford basement into a mock prison and recruited participants for an experiment. Nine would be guards, nine would be prisoners, and six would be on call. He acted as the superintendent. Zimbardo terminated the experiment after less than a week because the guards became too sadistic and treated the prisoners like animals. One guard, Dave Eshelman, screamed at the prisoners to “fuck the floor” and humiliated them by making them pretend to be in love with Mrs. Frankenstein. Zimbardo appeared to have proven that when people are put into an evil place (the basement included small cells, solitary confinement, and the prisoners wore chains) and surrounded by evil influences (himself and the other guards), they act in evil ways.

Led by psychology professor Phillip Zimbardo in 1971. In one of the most controversial psychology experiments ever, college students were assigned the role of prisoner and prison guards. The Stanford Prison Experiment, led by psychology professor Phillip Zimbardo in 1971. In one of the most controversial psychology experiments ever, college students were assigned the role of prisoner and prison guards. Zimbardo and his group wanted to see whether the brutality among prison guards in American prisons was due to dispositional personalities of guards or whether it had to do with the prison environment. Zimbardo and his group chose 24 of 75 applicants who were judged the most physically and mentally stable and the least involved in antisocial behaviors. They were all paid $15 to take part in the experiment, but had no idea what the experiment was about. Prisoners were treated like criminals, being arrested from their homes and taken to a police station, and then blindfolded to go to the basement of the psychology department at Stanford, where Zimbardo set with barred doors and windows, bare walls and small cells — a prison environment to make prisoners feel deindividuated. Prisoners were not called by their names — only ID numbers to make them feel anonymous. Guards were dressed in uniforms of khakis, carrying whistles and billy club, and wore sunglasses to avoid eye contact with prisoners. Guards worked eight hour shifts and were instructed to do whatever they could to maintain law and order in the prison, but were not allowed.

They began with nine guards and nine prisoners in our jail. Three guards worked each of three eight-hour shifts, while three prisoners occupied each of the three barren cells around the clock. The remaining guards and prisoners from our sample of 24 were on call in case they were needed. The cells were so small that there was room for only three cots on which the prisoners slept or sat, with room for little else. Zimbardo and his group wanted to see whether the brutality among prison guards in American prisons was due to dispositional personalities of guards or whether it had to do with the prison environment.

In fact, this wasn’t the case. Dave Eshelman nicknamed 'John Wayne' after his swaggering, macho attitude, was the only guard who appeared to suffer from madness, group madness or otherwise. When speaking to Ronson, Eshelman admitted that he’d been faking his loss of control because the experiment was going nowhere in the early days and Eshelman was concerned that Zimbardo wasn’t going to get good results. He acted evil—channeling the sadistic prison warden in Cool Hand Luke—to get the experiment started. The fact that Eshelman was acting doesn’t invalidate what happened—Eshelman chose to act in the way that he did for some psychological reason, and the prisoners still experienced brutality regardless of its sincerity. However, the fact that Eshelman was motivated by wanting to help Zimbardo is the opposite of group madness—Eshelman wasn’t corrupted by an environment; he was trying to do “something good.”

The prisoners even nicknamed the most macho and brutal guard in our study "John Wayne." Later, we learned that the most notorious guard in a Nazi prison near Buchenwald was named "Tom Mix" – the John Wayne of an earlier generation – because of his "Wild West" cowboy macho image in abusing camp inmates. Where had our "John Wayne" learned to become such a guard? How could he and others move so readily into that role? How could intelligent, mentally healthy, "ordinary" men become perpetrators of evil so quickly? These were questions we were forced to ask.

Because the first day passed without incident, everyone was surprised and totally unprepared for the rebellion which broke out on the morning of the second day. The prisoners removed their stocking caps, ripped off their numbers, and barricaded themselves inside the cells by putting their beds against the door. And now the problem was, what were the guards going to do about this rebellion? The guards were very much angered and frustrated because the prisoners also began to taunt and curse them. When the morning shift of guards came on, they became upset at the night shift who, they felt, must have been too lenient. The guards had to handle the rebellion themselves, and what they did was fascinating for the staff to behold.

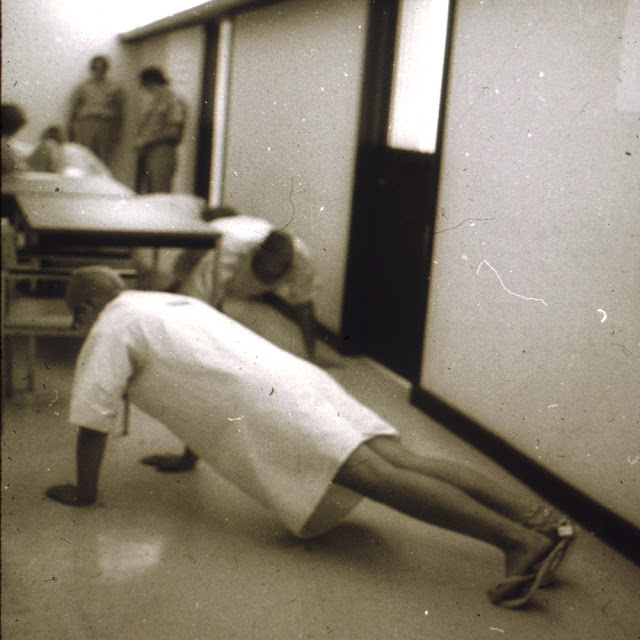

Guards sprayed fire exstinguishers into the cells when they resisted. The three back up guards were even called in to regain control cose it was going so wrong. Sleep interuption, the prisoners were striped naked, they were not allowed to shower, paper bags were put over their heads, they had to do exercises even at 2am, ritualistic humiliation was now all on the cards. All these mind games quickly escalated. The prisoners were later forced to choose between keeping their blanketsor letting a fellowe prisoner out The Hole from solitary confinement. Dave Eshelman aka 'John Wayne' was the one who also made them do push up when they couldnt remember their new given numbers. He was extremely inventive with his cruelty. Arbitrarily subjecting them to embarrassing sexual innuendo, solitary confinement for little mistakes.

Guards sprayed fire exstinguishers into the cells when they resisted. The three back up guards were even called in to regain control cose it was going so wrong. Sleep interuption, the prisoners were striped naked, they were not allowed to shower, paper bags were put over their heads, they had to do exercises even at 2am, ritualistic humiliation was now all on the cards. All these mind games quickly escalated. The prisoners were later forced to choose between keeping their blanketsor letting a fellowe prisoner out The Hole from solitary confinement. Dave Eshelman aka 'John Wayne' was the one who also made them do push up when they couldnt remember their new given numbers. He was extremely inventive with his cruelty. Arbitrarily subjecting them to embarrassing sexual innuendo, solitary confinement for little mistakes.An ex-convict consultants later informed the staff that a similar tactic is used by real guards in real prisons to break prisoner alliances. For example, racism is used to pit Blacks, Chicanos, and Anglos against each other. In fact, in a real prison the greatest threat to any prisoner's life comes from fellow prisoners. By dividing and conquering in this way, guards promote aggression among inmates, thereby deflecting it from themselves. The prisoners' rebellion also played an important role in producing greater solidarity among the guards. Now, suddenly, it was no longer just an experiment, no longer a simple simulation. Instead, the guards saw the prisoners as troublemakers who were out to get them, who might really cause them some harm. In response to this threat, the guards began stepping up their control, surveillance, and aggression. The guards were especially tough on the ringleader of the rebellion, Prisoner #5401. He was a heavy smoker, and they controlled him by regulating his opportunity to smoke. We later learned, while censoring the prisoners' mail, that he was a self-styled radical activist. He had volunteered in order to "expose" our study, which he mistakenly thought was an establishment tool to find ways to control student radicals. In fact, he had planned to sell the story to an underground newspaper when the experiment was over! However, even he fell so completely into the role of prisoner that he was proud to be elected leader of the Stanford County Jail Grievance Committee, as revealed in a letter to his girlfriend.

Prisoner #8612 wad the first to crack. Less than 36 hours into the experiment, he began suffering from acute emotional disturbance, disorganized thinking, uncontrollable crying, and rage. In spite of all of this, we had already come to think so much like prison authorities that we thought he was trying to "con" us – to fool us into releasing him. When our primary prison consultant interviewed Prisoner #8612, the consultant chided him for being so weak, and told him what kind of abuse he could expect from the guards and the prisoners if he were in San Quentin Prison. He had a full blown breakdown, even trying to act crazy but in the end he completely lost it. Dr Zimbardo even tried to make #8612 a snitch to calm him down. During the next count, Prisoner #8612 told other prisoners, "You can't leave. You can't quit." That sent a chilling message and heightened their sense of really being imprisoned. #8612 then began to act "crazy," to scream, to curse, to go into a rage that seemed out of control. in the end he was asked to leave.

At first the prisoners showed solidarity by refusing to eat the special privilidge foods, or by refusing to leave The Hole if the matresses weren't returned to the other prisoners. In retaliation the guards made them do slow push up's, sit up's and jumping Jack's. Going to the toilet was soon denied after their 10pm curfew so each cell was given a bucket which wasnt allowed to be emptied so by morning the cells started to smell. On visiting day (day 3) families were allowed to see their sons. Worried that when the parents saw the state of our jail, they might insist on taking their sons home. To counter this, staff manipulated both the situation and the visitors by making the prison environment seem pleasant and benign. They washed, shaved, and groomed the prisoners, had them clean and polish their cells, fed them a big dinner, played music on the intercom, and even had an attractive former Stanford cheerleader, Susie Phillips, greet the visitors at the registration desk. Before any parents could enter the visiting area, they also had to discuss their son's case with the Warden. Of course, parents complained about these arbitrary rules, but remarkably, they complied with them. And so they, too, became bit players in the prison drama, being good middle-class adults. When one mother said she had never seen her son looking so bad, they responded by shifting the blame from the situation to her son. "What's the matter with your boy? Doesn't he sleep well?" Then they asked the father, "Don't you think your boy can handle this?" He bristled, "Of course he can – he's a real tough kid, a leader." Turning to the mother, he said, "Come on Honey, we've wasted enough time already." And to the staff, "See you again at the next visiting time.

A rumour circulated that #6812 would come back to rescue the remaining prisoners so the guards had to move the prison from the basement into an upstairs department floor. When prisoner #819 was about to be sent home the guards made the other prisoners shout ''#819 is a bad prisoner.'' The guards also sprayed fire exstinguishers into the cells when the prisoners barricaded themselves inside the cells with their matresses. The guards then used psychologicals tactics such as offering special privilidge meals to three of the prisoners, they ate while the other prisoners watched, were allowed to wash and brush their teeth, and to wear their uniforms in the ''good cell''. After 12 hours they were sent back into the regular cell that lacked beds.

At this point in the study, a Catholic priest who had been a prison chaplain to evaluate how realistic the prison situation was, and the result was truly Kafkaesque. The chaplain interviewed each prisoner individually, and in amazement half the prisoners introduced themselves by number rather than name. After some small talk, he popped the key question: "Son, what are you doing to get out of here?" When the prisoners responded with puzzlement, he explained that the only way to get out of prison was with the help of a lawyer. He then volunteered to contact their parents to get legal aid if they wanted him to, and some of the prisoners accepted his offer.

The priest's visit further blurred the line between role-playing and reality. In daily life this man was a real priest, but he had learned to play a stereotyped, programmed role so well – talking in a certain way, folding his hands in a prescribed manner – that he seemed more like a movie version of a priest than a real priest, thereby adding to the uncertainty they were all feeling about where our roles ended and our personal identities began.

The only prisoner who did not want to speak to the priest was Prisoner #819, who was feeling sick, had refused to eat, and wanted to see a doctor rather than a priest. Eventually he was persuaded to come out of his cell and talk to the priest and superintendent so we could see what kind of a doctor he needed. While talking to them, he broke down and began to cry hysterically, just as had the other two boys we released earlier. They took the chain off his foot, the cap off his head, and told him to go and rest in a room that was adjacent to the prison yard. He was given some food and then taken to see a doctor.

The next day, all prisoners who thought they had grounds for being paroled were chained together and individually brought before the Parole Board. The Board was composed mainly of people who were strangers to the prisoners (departmental secretaries and graduate students) and was headed by the top prison consultant. Several remarkable things occurred during these parole hearings. First, when they asked prisoners whether they would forfeit the money they had earned up to that time if they were to parole them, most said yes. Then, when they ended the hearings by telling prisoners to go back to their cells while they considered their requests, every prisoner obeyed, even though they could have obtained the same result by simply quitting the experiment. Why did they obey? Because they felt powerless to resist. Their sense of reality had shifted, and they no longer perceived their imprisonment as an experiment. In the psychological prison they had created, only the correctional staff had the power to grant paroles. During the parole hearings they also witnessed an unexpected metamorphosis of our prison consultant as he adopted the role of head of the Parole Board. He literally became the most hated authoritarian official imaginable, so much so that when it was over he felt sick at who he had become – his own tormentor who had previously rejected his annual parole requests for 16 years when he was a prisoner.

By day #4 the guards were angry about wasting their time dissasembling the prison and even missed their lunch. Now prisoners were made to do longer push up's and made to clean toilets with their bare hands and polish the guards shoes.

When the new prisoner #416 went on a hunger strike the guards made the prisoners do push up's while #416 sang Amazing Grace. Prisoners coped with their feelings of frustration and powerlessness in a variety of ways. At first, some prisoners rebelled or fought with the guards. Four prisoners reacted by breaking down emotionally as a way to escape the situation. One prisoner developed a psychosomatic rash over his entire body when he learned that his parole request had been turned down. Others tried to cope by being good prisoners, doing everything the guards wanted them to do. Prisoner #2093 was nicknamed 'Sarge' for being a model prisoner. There were 3 types of guards: the nice one who felt sorry for the prisoners and did little favours, the tough but fair guard, and the sadistic guard John Wayne who constantly degraded and humiliated the prisoners. He even put the prisoners blankets in nettles so it would take them hours to remove them if they wanted to sleep.

By day 5 the guards had total control and even dictated a letter to the prisoners to write to their families:

''Dear mom & dad, Im having a marvelous time, food is great and there is always a lot of fun & games. The officers have treated me well, they are all swell guys, you would like them. No need to visit because its 7th heaven. - Yours always #7258''

John Wayne would also force the prisoners to repeat things:

''In the future you do the work when you're told

Thank you Mr Correctional Officer

Say it again!

Thank you Mr Correctional Officer

Say bless you Mr Correctional Officer

Bless you Mr Correctional Officer''

Even Sarge was abused:

''Why do you try and be obedient so much?

I dont know its my nature to be obedient correctional officer.

You're a liar, you're a stinking liar.

If you say so Mr correctional officer.

What if I told u to get down on the floor, and fuck the floor? What would you do then.

I would say I didnt know how Mr Correctional officer.''

Prisoner #416 kept up his hunger strike and was thrown in the hole holding the sausages that he refused to eat. John Wayne even hit him in the face with a sausage. The guards threaten to cancel visiting hours if #416 didnt eat his sausages. #416 refused again. The guards then had the prisoners express their anger at #416 while he was sitting in the hole behind the door in total darkness ''thank you #416''. He was kept in solitary confinement for 3hr even though 1hr was the limit.

John Wayne then made #416 put his hands in the air then role play being Frankenstein to walk over to another prisoner pretending to be the Bride of Frankenstein and say ''i love you #2093''. He then yelled at #416 to ' walk like Frankenstein', I didnt tell you to walk like you!" and to hug and kiss. "Get up close''. When #2093 refused to kiss he was made to do push up's.

#416 once again refused to eat his sausages. By now he was dirty from being on the floor so much. John Wayne decided to give the prisoners a choice:

''Now theres a couple of ways we can do this depending on what you wanna do. If #416 does not wanna eat his sausages then you can give me the blanket and sleep on your mattress or you can keep you blanket and #416 will stay in another day, now what will it be?.'' ''Im gonna keep my blanket''. ''You boys need to come to some sort of a decision.'' ''We got 3 against 1. Ok keep your blankets, #416 your gonna be in there for a while so just get used to it.''

The prisoners displayed 3 types of behaviour. At first they rebelled and faught the guards, then by day 4 they became passive, and 4 prisoners broke down and cried, while others became model prisoners.

"After the first day I noticed nothing was happening. It was a bit of a bore, so I made the decision I would take on the persona of a very cruel prison guard," said Dave Eshleman, one of the wardens who took a lead role.

At the same time the prisoners, referred to only by their numbers and treated harshly, rebelled and blockaded themselves inside their cells. The guards saw this as a challenge to their authority, broke up the demonstration and began to impose their will. "Suddenly, the whole dynamic changed as they believed they were dealing with dangerous prisoners, and at that point it was no longer an experiment," said Prof Zimbardo. It began by stripping them naked, putting bags over their heads, making them do press-ups or other exercises and humiliating them. "The most effective thing they did was simply interrupt sleep, which is a known torture technique," said Clay Ramsey, one of the prisoners. "What was demanded of me physically was way too much and I also felt that there was really nobody rational at the wheel of this thing so I started refusing food."

"It was rapidly spiralling out of control," said prison guard Mr Eshleman who hid behind his mirrored sunglasses and a southern US accent. "I kept looking for the limits - at what point would they stop me and say 'No, this is only an experiment and I have had enough', but I don't think I ever reached that point."

The abusive prison guard, Mr Eshleman, also felt he gained something from the experiment. "I learned that in a particular situation I'm probably capable of doing things I will look back on with some shame later on," he said. "When I saw the pictures coming from Abu Ghraib in Iraq, it immediately struck me as being very familiar to me and I knew immediately they were probably just very ordinary people and not the bad apples the defence department tried to paint them as. "I did some horrible things, so if I ever had the chance to repeat the experiment I wouldn't do it."

On the fifth night, some visiting parents asked to contact a lawyer in order to get their son out of prison. They said a Catholic priest had called to tell them they should get a lawyer or public defender if they wanted to bail their son out! A lawyer was called as requested, and he came the next day to interview the prisoners with a standard set of legal questions, even though he, too, knew it was just an experiment. At this point it became clear that they had to end the study. They had created an overwhelmingly powerful situation – a situation in which prisoners were withdrawing and behaving in pathological ways, and in which some of the guards were behaving sadistically. Even the "good" guards felt helpless to intervene, and none of the guards quit while the study was in progress. Indeed, it should be noted that no guard ever came late for his shift, called in sick, left early, or demanded extra pay for overtime work.

On the fifth night, some visiting parents asked to contact a lawyer in order to get their son out of prison. They said a Catholic priest had called to tell them they should get a lawyer or public defender if they wanted to bail their son out! A lawyer was called as requested, and he came the next day to interview the prisoners with a standard set of legal questions, even though he, too, knew it was just an experiment. At this point it became clear that they had to end the study. They had created an overwhelmingly powerful situation – a situation in which prisoners were withdrawing and behaving in pathological ways, and in which some of the guards were behaving sadistically. Even the "good" guards felt helpless to intervene, and none of the guards quit while the study was in progress. Indeed, it should be noted that no guard ever came late for his shift, called in sick, left early, or demanded extra pay for overtime work.On the last day, a series of encounter sessions were held, first with all the guards, then with all the prisoners (including those who had been released earlier), and finally with the guards, prisoners, and staff together. They did this in order to get everyone's feelings out in the open, to recount what they had observed in each other and ourselves, and to share our experiences, which to each of us had been quite profound. They also tried to make this a time for moral reeducation by discussing the conflicts posed by this simulation and our behavior. For example, they reviewed the moral alternatives that had been available to us, so that they would be better equipped to behave morally in future real-life situations, avoiding or opposing situations that might transform ordinary individuals into willing perpetrators or victims of evil.